Research Interests

The Castel laboratory is interested in the molecular mechanisms underlying oncoprotein-mediated transformation.

Our laboratory uses biochemical, cell signaling, mouse models, and pharmacological approaches to elucidate the functions and regulation of different oncoproteins in cancer and congenital disorders.

We are particularly interested in the RAS family of GTPases, which are involved in mitogenic signaling and are notorious drivers of cancer and neurodevelopmental syndromes.

Focus 1: Regulation of RAS Signaling Components by Ubiquitination and Proteasomal Degradation

Our lab investigates the biochemical properties and cellular mechanisms of the RAS family of small GTPases.

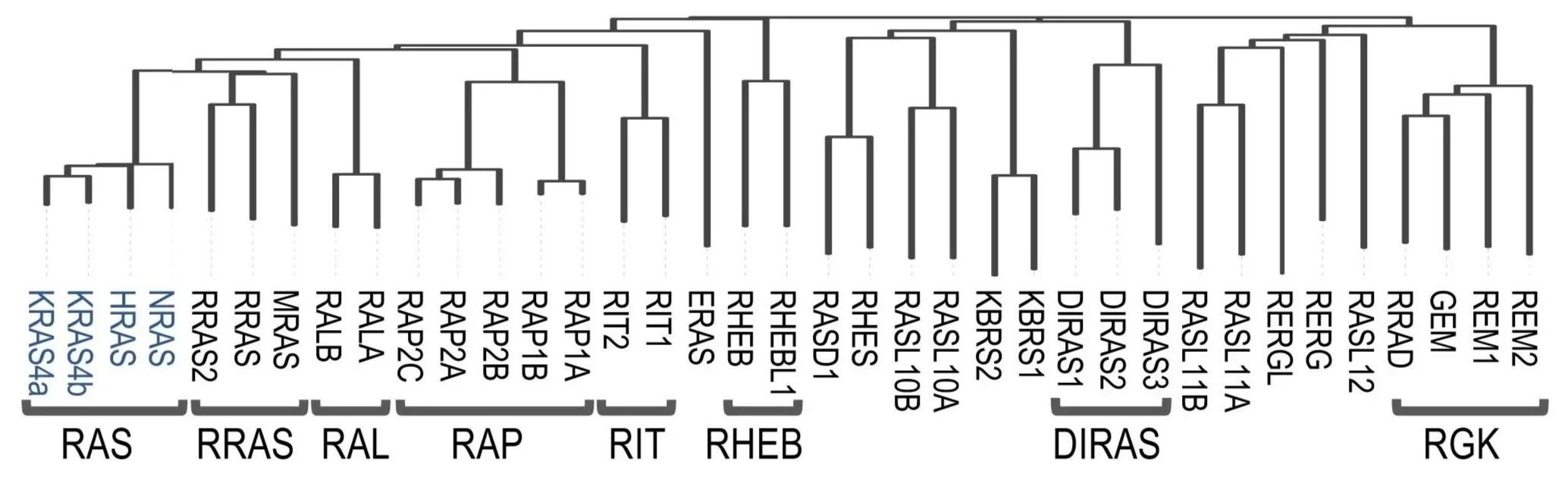

While decades of research have centered on the so-called classical RAS GTPases (KRAS, NRAS, and HRAS), these represent only a small subset of a much larger family comprising 36 members, many of which remain poorly characterized.

Recent studies, including work from our own lab, suggest that not all RAS family members are regulated by the typical mechanisms of nucleotide cycling. For several of these “non-canonical” GTPases, the absence of identified GAPs or GEFs, and their low affinity to nucleotides, hints at alternative modes of regulation that may underlie distinct signaling outputs and cellular functions.

Some of the work in our lab aims to uncover these mechanisms to better understand how RAS family diversity shapes cellular signaling and disease biology.

Conservation of the different members of the RAS GTPase family (Mozzarelli et al. 2024 Mol Cell).

One alternative regulatory mechanism that our lab is particularly interested in is ubiquitination and proteolysis.

While classical RAS GTPases are best known for their regulation through rapid nucleotide cycling and membrane-targeting modifications, it has been shown that some RAS family members can be controlled at the post-translational level through ubiquitin-dependent pathways.

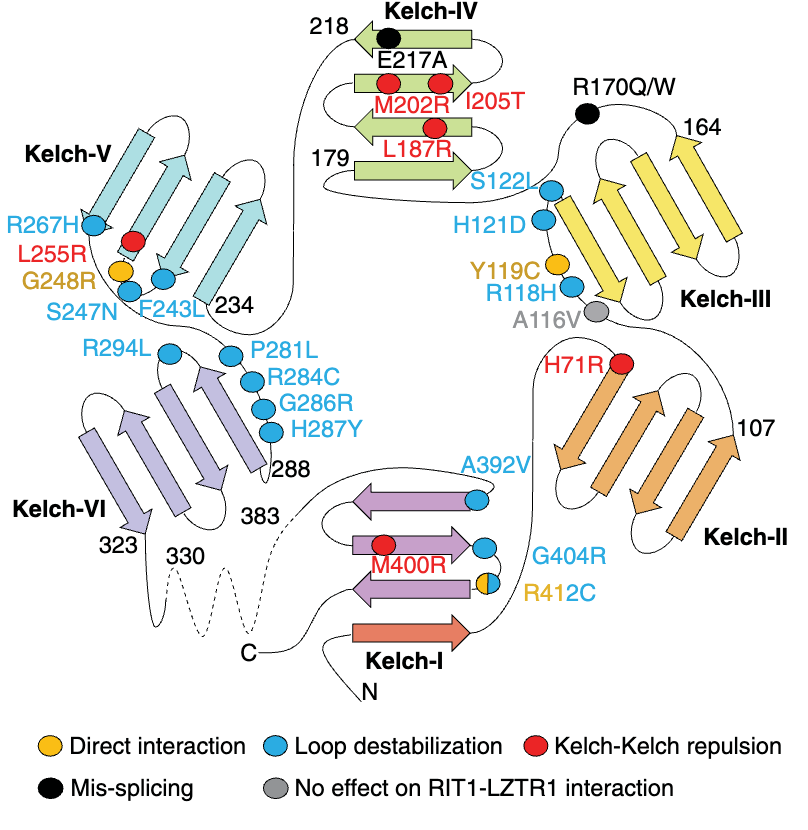

For instance, we and others have identified that the RAS GTPase RIT1 can be regulated by LZTR1, a substrate adaptor for the Cullin-3 E3 ubiquitin ligase. Importantly, pathogenic mutations in the LZTR1 gene have been linked to several human conditions, such as cancer, schwannomatosis, and Noonan syndrome.

LZTR1 contains an N-terminal Kelch domain, which consists of several Kelch repeats (or blades) that form a ß-propeller structure responsible for substrate recognition.

Recently, in collaboration with Dr. Simanshu’s group at NCI, we have uncovered the structural mechanisms that explain why certain mutations on the Kelch domain fail to recognize RIT1, leading to its accumulation in the cell as a result of defective degradation. LZTR1 also contains two C-terminal BTB-BACK domains, which function as a dimerization platform and region of Cullin 3 interaction.

Schematic representation of the different loss-of-function mechanisms for several pathogenic LZTR1 mutations (Dharmaiah, Bonsor, Mo et al, 2025 Science).

Focus 2: Development of Cellular and Mouse Models that Recapitulate RAS-Driven Diseases

RAS GTPases are involved in many human conditions, including cancer and developmental disorders.

Under physiological conditions, RAS activation is transient and tightly regulated by upstream receptor tyrosine kinases and downstream effectors. However, as a result of pathogenic mutations, the function of RAS GTPases becomes dysregulated, driving constitutive downstream signaling, uncontrolled growth and malignant transformation.

Mutations in RAS genes are among the most frequent oncogenic events in human cancer, occurring in approximately 30% of all tumors and representing a leading cause of mortality worldwide. These mutations are particularly prevalent in pancreatic, colorectal, and lung cancers, where they define distinct biological subtypes and influence therapeutic response.

Despite being discovered more than four decades ago, RAS-driven cancers remain exceptionally difficult to treat, reflecting the need for accurate experimental systems that model their complexity.

In addition, germline pathogenic variants in genes of the RAS/MAPK pathway are involved in a group of neurodevelopmental disorders termed RASopathies.

This group of disorders are characterized by systemic manifestations, such as cardiovascular abnormalities, musculoskeletal defects, and predisposition to malignancies, among many others.

Some of these conditions include:

Noonan syndrome

Costello syndrome

Cardiofaciocutaneous syndrome

Neurofibromatosis type 1

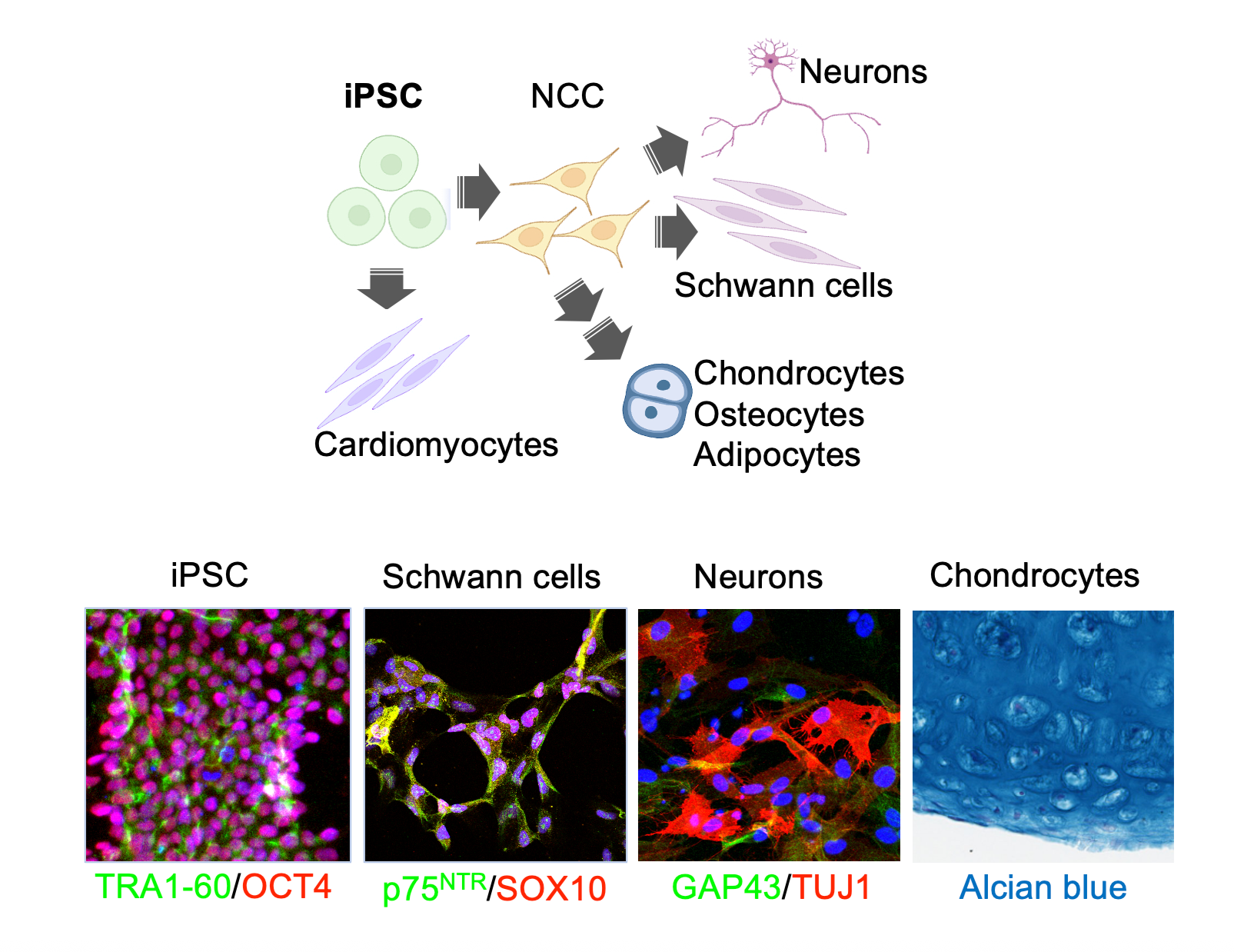

Using iPSCs and specific differentiation protocols, we can establish different cellular lineages that allow the study of RAS GTPase signaling in specific cellular contexts.

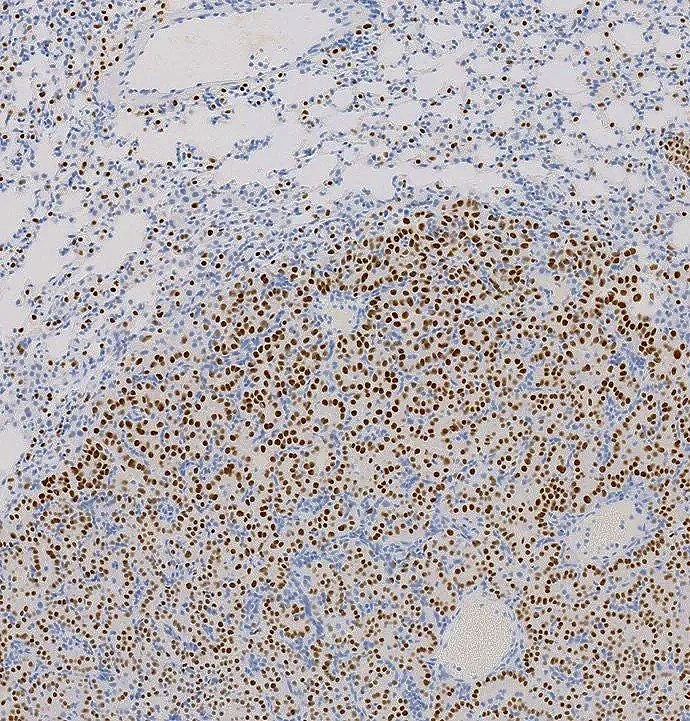

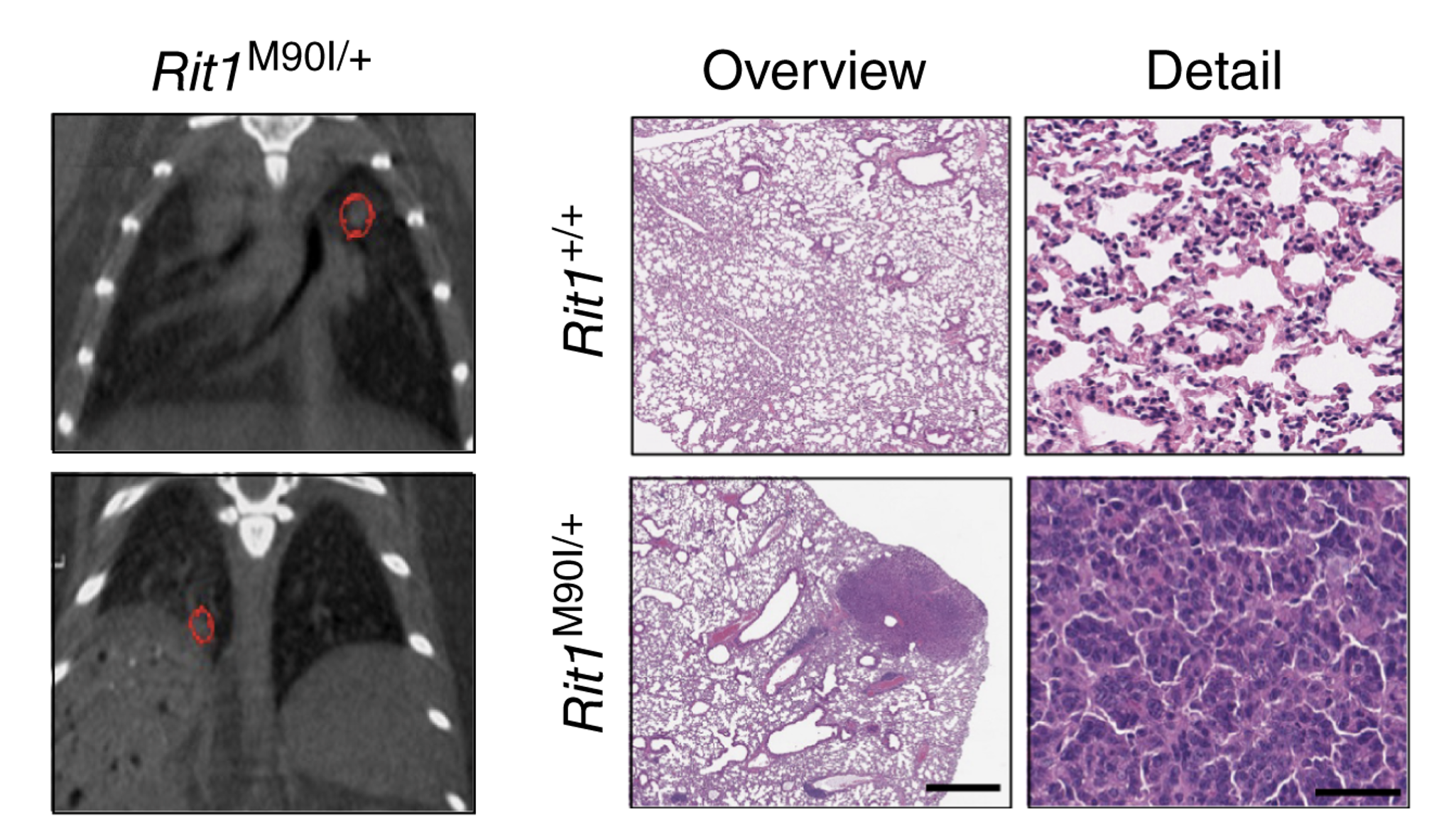

Using a knock-in mouse model that expresses a RIT1 pathogenic variant, we have established mouse models for a rare subtype of lung adenocarcinoma (shown here by µCT and histology) and Noonan syndrome.

As part of our research, we work in developing and refining cellular and mouse models that faithfully recapitulate these RAS-driven diseases.

Using advanced genetic engineering approaches, including CRISPR/Cas9-mediated editing, conditional knock-in alleles, and inducible expression systems, we introduce specific mutations in RAS genes (or their regulators) in a tissue-specific and temporally controlled manner. These models allow us to dissect how distinct RAS mutations influence disease initiation, progression, and therapeutic response.

For example, we have recently developed mouse models of lung adenocarcinoma and Noonan syndrome driven by mutations in the RAS GTPase RIT1 and have identified therapies that could be used in the clinical setting to treat these conditions.

Complementary in vitro systems, including isogenic cell lines and induced-pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), are also employed in our lab.

The latter are particularly interesting for the study of germline syndromes, such as the RASopathies, because it allows us to establish different cellular lineages from parent isogenic iPSCs.

Together, these approaches provide a versatile and physiologically relevant platform to study RAS biology and to evaluate emerging targeted therapies in preclinical settings.

Focus 3: RAS Effectors and Their Contribution to Disease

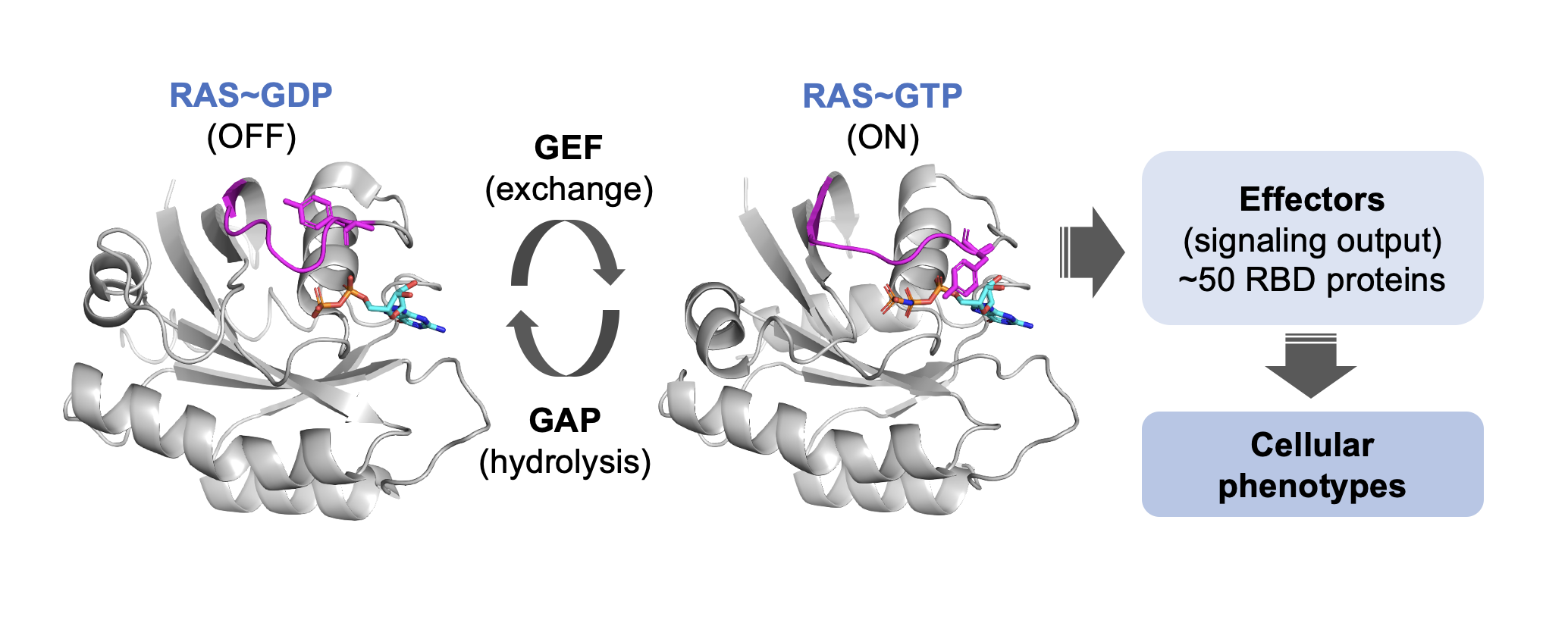

RAS GTPases function as molecular switches that cycle between a GDP or GTP-bound state.

Upon binding to GTP, RAS proteins adopt an active conformation that enables interaction with a variety of downstream effector proteins, most of which contain conserved RAS-binding domains (RBD, RA).

These effectors translate RAS activation into diverse signaling outcomes, controlling key cellular processes such as proliferation, differentiation, and survival among others.

While the core mechanisms of RAS activation and inactivation are well characterized, our understanding of how RAS selectively engages specific effectors remains incomplete. Despite extensive in vitro characterization of RAS effectors, studies that investigate their physiological roles in vivo, especially during development and disease, are still under-explored.

Critical challenges in studying RAS effectors include:

RAS-effector interactions are governed not only by affinity, but also by local concentration, post-translational modifications, and subcellular compartmentalization.

Moreover, competition among effectors for limited pools of active RAS adds another layer of regulatory complexity that shapes signaling output and cellular responses.

Some of the research in our lab aims to elucidate how distinct RAS effectors contribute to tumor initiation, progression, and therapeutic response using genetic, biochemical, and in vivo approaches.

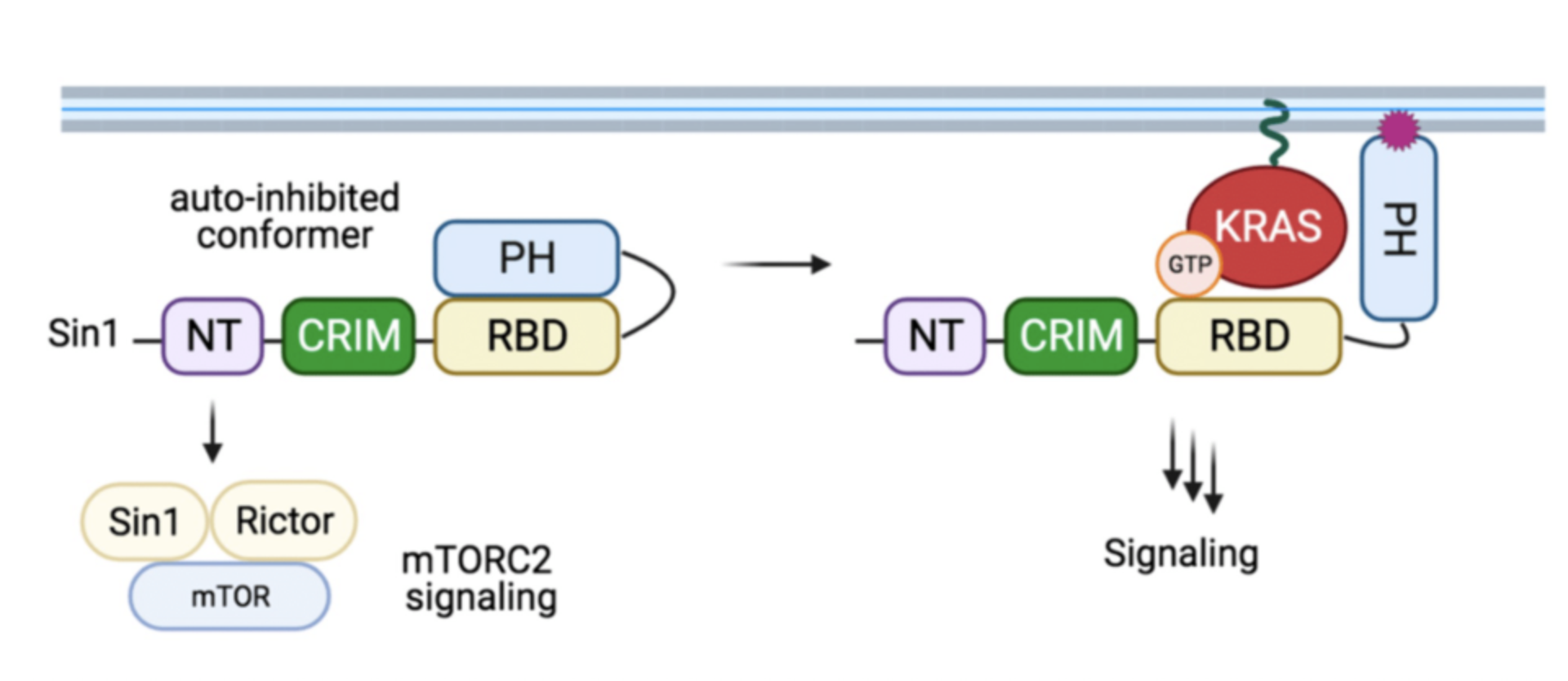

Proposed model of Sin1 function. In the autoinhibited conformation, Sin1 is unable to bind to KRAS, but can participate as a component of mTORC2. In the open conformation, Sin1 is able to bind KRAS-GTP, but the signaling downstream of this GTPase remain unknown.

RAS GTPases are binary switches that promote signaling upon binding to downstream RAS effectors.

Recent work in this context includes the biochemical characterization of Sin1, a novel and atypical KRAS-specific effector. Although Sin1 has been extensively characterized as a core component of the mTOR complex 2 (mTORC2), our work revealed that Sin1 might be an effector of KRAS independently of mTORC2 and ongoing work in the lab is trying to identify such alternative pathways.

We have also recently studied the biochemical and biophysical properties of CRAF as a neomorphic effector of oncogenic RIT1.

Currently, we are working on identifying and characterizing novel RAS effectors, particularly for RAS GTPases that are less understood and in the in vivo context. By dissecting effector-specific signaling networks, we seek to uncover novel vulnerabilities in RAS-driven cancers and other diseases linked to aberrant RAS pathway activation.